Avalanche Consensus

Learn about the groundbreaking Avalanche Consensus algorithms.

Consensus is the task of getting a group of computers (a.k.a. nodes) to come to an agreement on a decision. In blockchain, this means that all the participants in a network have to agree on the changes made to the shared ledger.

This agreement is reached through a specific process, a consensus protocol, that ensures that everyone sees the same information and that the information is accurate and trustworthy.

Avalanche Consensus

Avalanche Consensus is a consensus protocol that is scalable, robust, and decentralized. It combines features of both classical and Nakamoto consensus mechanisms to achieve high throughput, fast finality, and energy efficiency. For the whitepaper, see here.

Key Features Include:

- Speed: Avalanche consensus provides sub-second, immutable finality, ensuring that transactions are quickly confirmed and irreversible.

- Scalability: Avalanche consensus enables high network throughput while ensuring low latency.

- Energy Efficiency: Unlike other popular consensus protocols, participation in Avalanche consensus is neither computationally intensive nor expensive.

- Adaptive Security: Avalanche consensus is designed to resist various attacks, including sybil attacks, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and collusion attacks. Its probabilistic nature ensures that the consensus outcome converges to the desired state, even when the network is under attack.

Conceptual Overview

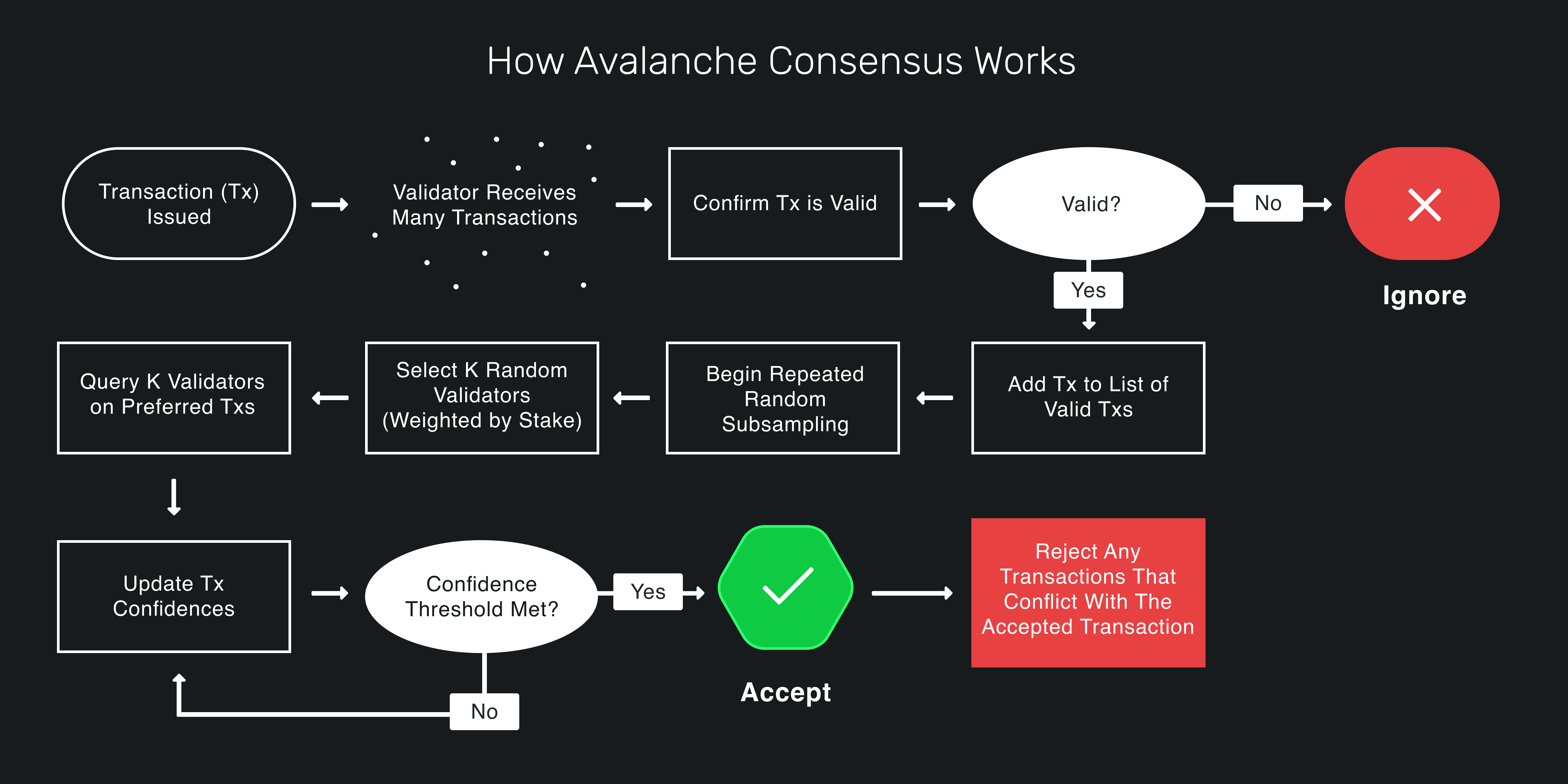

Consensus protocols in the Avalanche family operate through repeated sub-sampled voting. When a node is determining whether a transaction should be accepted, it asks a small, random subset of validator nodes for their preference. Each queried validator replies with the transaction that it prefers, or thinks should be accepted.

Note

Consensus will never include a transaction that is determined to be invalid. For example, if you were to submit a transaction to send 100 AVAX to a friend, but your wallet only has 2 AVAX, this transaction is considered invalid and will not participate in consensus.

If a sufficient majority of the validators sampled reply with the same preferred transaction, this becomes the preferred choice of the validator that inquired.

In the future, this node will reply with the transaction preferred by the majority.

The node repeats this sampling process until the validators queried reply with the same answer for a sufficient number of consecutive rounds.

- The number of validators required to be considered a "sufficient majority" is referred to as "α" (alpha).

- The number of consecutive rounds required to reach consensus, a.k.a. the "Confidence Threshold," is referred to as "β" (beta).

- Both α and β are configurable.

When a transaction has no conflicts, finalization happens very quickly. When conflicts exist, honest validators quickly cluster around conflicting transactions, entering a positive feedback loop until all correct validators prefer that transaction. This leads to the acceptance of non-conflicting transactions and the rejection of conflicting transactions.

Avalanche Consensus guarantees that if any honest validator accepts a transaction, all honest validators will come to the same conclusion.

Note

For a great visualization, check out this demo.

Deep Dive Into Avalanche Consensus

Intuition

First, let's develop some intuition about the protocol. Imagine a room full of people trying to agree on what to get for lunch. Suppose it's a binary choice between pizza and barbecue. Some people might initially prefer pizza while others initially prefer barbecue. Ultimately, though, everyone's goal is to achieve consensus.

Everyone asks a random subset of the people in the room what their lunch preference is. If more than half say pizza, the person thinks, "OK, looks like things are leaning toward pizza. I prefer pizza now." That is, they adopt the preference of the majority. Similarly, if a majority say barbecue, the person adopts barbecue as their preference.

Everyone repeats this process. Each round, more and more people have the same preference. This is because the more people that prefer an option, the more likely someone is to receive a majority reply and adopt that option as their preference. After enough rounds, they reach consensus and decide on one option, which everyone prefers.

Snowball

The intuition above outlines the Snowball Algorithm, which is a building block of Avalanche consensus. Let's review the Snowball algorithm.

Parameters

- n: number of participants

- k (sample size): between 1 and n

- α (quorum size): between 1 and k

- β (decision threshold): >= 1

Algorithm

Algorithm Explained

Everyone has an initial preference for pizza or barbecue. Until someone has decided, they query k people (the sample size) and ask them what they prefer. If α or more people give the same response, that response is adopted as the new preference. α is called the quorum size. If the new preference is the same as the old preference, the consecutiveSuccesses counter is incremented. If the new preference is different then the old preference, the consecutiveSuccesses counter is set to 1. If no response gets a quorum (an α majority of the same response) then the consecutiveSuccesses counter is set to 0.

Everyone repeats this until they get a quorum for the same response β times in a row. If one person decides pizza, then every other person following the protocol will eventually also decide on pizza.

Random changes in preference, caused by random sampling, cause a network preference for one choice, which begets more network preference for that choice until it becomes irreversible and then the nodes can decide.

In our example, there is a binary choice between pizza or barbecue, but Snowball can be adapted to achieve consensus on decisions with many possible choices.

The liveness and safety thresholds are parameterizable. As the quorum size, α, increases, the safety threshold increases, and the liveness threshold decreases. This means the network can tolerate more byzantine (deliberately incorrect, malicious) nodes and remain safe, meaning all nodes will eventually agree whether something is accepted or rejected. The liveness threshold is the number of malicious participants that can be tolerated before the protocol is unable to make progress.

These values, which are constants, are quite small on the Avalanche Network. The sample size, k, is 20. So when a node asks a group of nodes their opinion, it only queries 20 nodes out of the whole network. The quorum size, α, is 14. So if 14 or more nodes give the same response, that response is adopted as the querying node's preference. The decision threshold, β, is 20. A node decides on choice after receiving 20 consecutive quorum (α majority) responses.

Snowball is very scalable as the number of nodes on the network, n, increases. Regardless of the number of participants in the network, the number of consensus messages sent remains the same because in a given query, a node only queries 20 nodes, even if there are thousands of nodes in the network.

Everything discussed to this point is how Avalanche is described in the Avalanche white-paper. The implementation of the Avalanche consensus protocol by Ava Labs (namely in AvalancheGo) has some optimizations for latency and throughput.

Blocks

A block is a fundamental component that forms the structure of a blockchain. It serves as a container or data structure that holds a collection of transactions or other relevant information. Each block is cryptographically linked to the previous block, creating a chain of blocks, hence the term "blockchain."

In addition to storing a reference of its parent, a block contains a set of transactions. These transactions can represent various types of information, such as financial transactions, smart contract operations, or data storage requests.

If a node receives a vote for a block, it also counts as a vote for all of the block's ancestors (its parent, the parents' parent, etc.).

Finality

Avalanche consensus is probabilistically safe up to a safety threshold. That is, the probability that a correct node accepts a transaction that another correct node rejects can be made arbitrarily low by adjusting system parameters. In Nakamoto consensus protocol (as used in Bitcoin and Ethereum, for example), a block may be included in the chain but then be removed and not end up in the canonical chain. This means waiting an hour for transaction settlement. In Avalanche, acceptance/rejection are final and irreversible and only take a few seconds.

Optimizations

It's not safe for nodes to just ask, "Do you prefer this block?" when they query validators. In Ava Labs' implementation, during a query a node asks, "Given that this block exists, which block do you prefer?" Instead of getting back a binary yes/no, the node receives the other node's preferred block.

Nodes don't only query upon hearing of a new block; they repeatedly query other nodes until there are no blocks processing.

Nodes may not need to wait until they get all k query responses before registering the outcome of a poll. If a block has already received alpha votes, then there's no need to wait for the rest of the responses.

Validators

If it were free to become a validator on the Avalanche network, that would be problematic because a malicious actor could start many, many nodes which would get queried very frequently. The malicious actor could make the node act badly and cause a safety or liveness failure. The validators, the nodes which are queried as part of consensus, have influence over the network. They have to pay for that influence with real-world value in order to prevent this kind of ballot stuffing. This idea of using real-world value to buy influence over the network is called Proof of Stake.

To become a validator, a node must bond (stake) something valuable (AVAX). The more AVAX a node bonds, the more often that node is queried by other nodes. When a node samples the network it's not uniformly random. Rather, it's weighted by stake amount. Nodes are incentivized to be validators because they get a reward if, while they validate, they're sufficiently correct and responsive.

Avalanche doesn't have slashing. If a node doesn't behave well while validating, such as giving incorrect responses or perhaps not responding at all, its stake is still returned in whole, but with no reward. As long as a sufficient portion of the bonded AVAX is held by correct nodes, then the network is safe, and is live for virtuous transactions.

Big Ideas

Two big ideas in Avalanche are subsampling and transitive voting.

Subsampling has low message overhead. It doesn't matter if there are twenty validators or two thousand validators; the number of consensus messages a node sends during a query remains constant.

Transitive voting, where a vote for a block is a vote for all its ancestors, helps with transaction throughput. Each vote is actually many votes in one.

Loose Ends

Transactions are created by users which call an API on an AvalancheGo full node or create them using a library such as AvalancheJS.

Other Observations

Conflicting transactions are not guaranteed to be live. That's not really a problem because if you want your transaction to be live then you should not issue a conflicting transaction.

Snowman is the name of Ava Labs' implementation of the Avalanche consensus protocol for linear chains.

If there are no undecided transactions, the Avalanche consensus protocol quiesces. That is, it does nothing if there is no work to be done. This makes Avalanche more sustainable than Proof-of-work where nodes need to constantly do work.

Avalanche has no leader. Any node can propose a transaction and any node that has staked AVAX can vote on every transaction, which makes the network more robust and decentralized.

Why Do We Care?

Avalanche is a general consensus engine. It doesn't matter what type of application is put on top of it. The protocol allows the decoupling of the application layer from the consensus layer. If you're building a dapp on Avalanche then you just need to define a few things, like how conflicts are defined and what is in a transaction. You don't need to worry about how nodes come to an agreement. The consensus protocol is a black box that put something into it and it comes back as accepted or rejected.

Avalanche can be used for all kinds of applications, not just P2P payment networks. Avalanche's Primary Network has an instance of the Ethereum Virtual Machine, which is backward compatible with existing Ethereum Dapps and dev tooling. The Ethereum consensus protocol has been replaced with Avalanche consensus to enable lower block latency and higher throughput.

Avalanche is very performant. It can process thousands of transactions per second with one to two second acceptance latency.

Summary

Avalanche consensus is a radical breakthrough in distributed systems. It represents as large a leap forward as the classical and Nakamoto consensus protocols that came before it. Now that you have a better understanding of how it works, check out other documentations for building game-changing Dapps and financial instruments on Avalanche.

Last updated on